A Breakthrough in Global Dynamics on Graphs

SLMath - October 2025

Siobhan Roberts

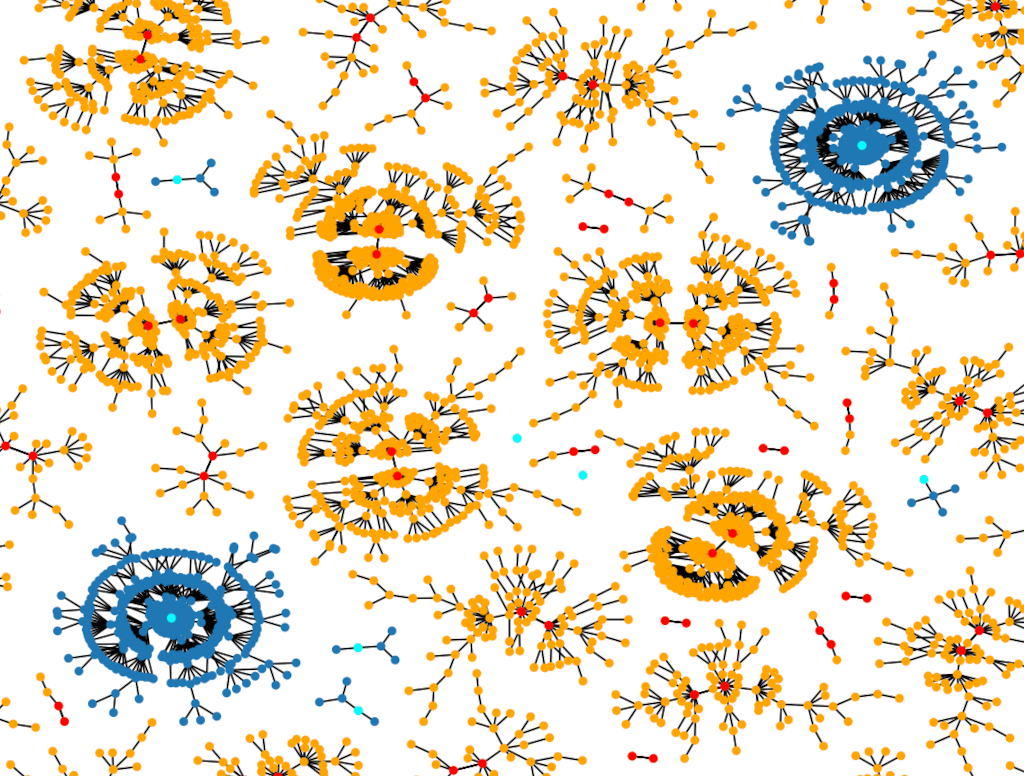

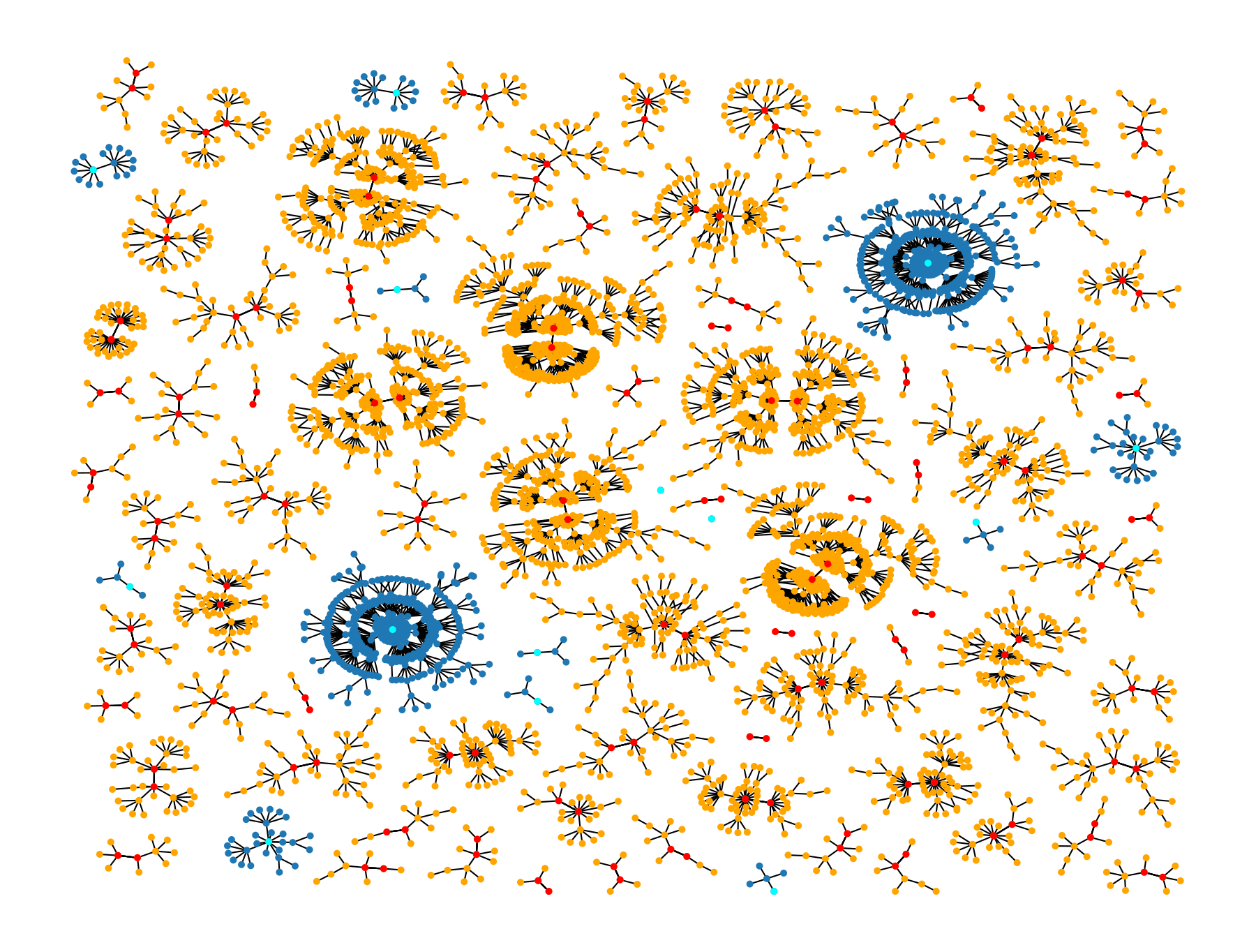

A random network is a mathematical model used to study systems wherein interconnections form by chance. Nodes represent objects or entities; edges represent interactions.

Mathematicians have successfully studied static equilibrium problems about network properties: What is a graph’s topology of nodes and edges? What probability distribution does it exhibit? What are the likely linkage patterns?

It is more difficult to probe dynamic problems with time-dependent variables that capture change: How does a process evolve on a fixed graph?

Imagine a graph that represents a network of neurons in the human brain. Whether or not a neuron fires depends on the neurons it is connected to and whether they fire. “What is evolving dynamically on the graph might be the dynamics of memory retrieval,” said Lenka Zdeborová, a mathematician and physicist who leads the Statistical Physics of Computation Laboratory at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne.

Dr. Zdeborová visited the Simons Laufer Mathematical Sciences Institute for the Spring 2025 program on “Probability and Statistics of Discrete Structures.” During the program, she worked with three collaborators — her Ph.D. student Yatin Dandi, as well as the M.I.T. mathematician David Gamarnik and his Ph.D. student Francisco Pernice. Their research on a dynamics problem resulted in the paper, “Sequential Dynamics in Ising Spin Glasses.”

“It is a breakthrough in understanding how random networks evolve under very natural dynamical update rules,” Dr. Gamarnik said. “We can finally answer these types of questions quantitatively.”

The Stanford mathematician Amir Dembo, a participant in the program, was thrilled with this development. Over the years, Dr. Dembo (and collaborators) made intermittent progress on the dynamics problem from the statistical physics perspective. The new research adds another layer. “This is the beauty of SLMath,” he said. “You get inspired by learning about what other people are doing.”

Evolution over time

The motivation for these dynamical problems emerged from physics in the 1980s. Physicists worked with models studying the interaction and phase transitions of particles — specifically in spin glass, a metal alloy with a disordered magnetic structure. In 2021, the Italian theoretical physicist Giorgio Parisi won a share of the Nobel Prize for spin glass research. He developed a theory of random phenomena that applies to other complex systems in an equilibrium or static end state.

The theory applies not just in physics. “What amazes me is that these spin glass models are the perfect models for optimization problems in computer science,” Mr. Dandi said. “In artificial intelligence, machine learning and neural networks, for example, you often have a similar kind of randomness and disorder.”

In 2024, the French mathematician Michel Talagrand won the Abel Prize in part for verifying Dr. Parisi’s work with equations and proofs. Along the way, Dr. Talagrand developed powerful new mathematics.

With the static properties well understood, researchers turned their attention to the evolution of a system over time, moving from a starting state to an end state, say from high to low temperature. They focused on optimizing a key class of algorithms — including the random walk algorithm and the greedy algorithm. Said Dr. Gamarnik, “Arguably this is how nature and the universe solve optimization problems.”

And while within the static domain the math followed the physics, the SLMath team’s advancements essentially did both at once. “What we are doing is new both for mathematicians and for physicists: “We developed new dynamical equations and are proving them rigorously,” Dr. Zdeborová said.

The bigger dynamical picture

Dr. Zdeborová had tried to tackle the dynamical problem in 2010 but made limited headway. Then she turned to machine learning problems, studying how neural networks learn from data using the dynamical gradient descent algorithm.

About two years ago, Dr. Gamarnik and his student Mr. Pernice turned their attention to obtaining and understanding equations for dynamics on graphs. They made progress on a restricted version of the problem, using a technique from statistical physics to analyze an algorithm whereby nodes on a graph update their states sequentially one-by-one, with “one pass.” However, getting at the bigger dynamical picture via this tactic was impractical. Conversely, Dr. Gamarnik said, “If everybody updates their state simultaneously, we have mathematics for that.” The challenge was understanding what happens if updates happen asynchronously, which is prescribed by the dynamics under investigation.

In November 2024, when Mr. Dandi visited M.I.T., ideas began to coalesce.

For his Ph.D., Mr. Dandi had worked on machine learning, deep learning and neural networks, and it became apparent that applying such techniques would help with the dynamics problem. The trick was to reformulate the original problem and modify the algorithm. “You have a hammer, and you change the nail so that the hammer works,” Mr. Dandi said.

The team used a “block approximation” algorithm, which interpolates between synchronous (easier to study) and asynchronous (more challenging) algorithms: Chop up the graph into subgroups that update their status in a sequential round-robin. Using this tool, the first task was to re-derive the equations in the special case that Dr. Gamarnik and Mr. Pernice had already solved. The researchers then developed equations for the general problem, but they were full of errors and incomplete.

Once together at SLMath, the team constructed the proof and went deep into the equations. “Terms magically cancelled out,” said Mr. Pernice. “After a lot of work, we found several miraculous simplifications. The equation we have right now is something we can easily simulate on a computer.”

A tool for many problems

Broadly, the implications and applications inform questions about dynamical processes evolving in environments that are constrained in complex ways.

Dr. Gamarnik envisions possible applications in quantum computing, improving the behavior of its notoriously fragile memory states. “Creating a robust quantum computing system requires maintaining it in a fixed state in presence of decoherence,” he said. “The techniques we developed have potential applications to estimating such robustness guarantees.”

Mr. Dandi sees applications back in artificial intelligence, with machine learning and neural network algorithms — systems that often work very well, but why or how is understood; they are a black box. Advances in global dynamics on graphs, Mr. Dandi said, will provide “a toolbox, a new perspective for understanding neural networks.”

And while at SLMath the team engaged in exciting discussions with a number of other program participants who were serendipitously aligning on related and far-reaching research. “The reason we’re very excited,” Dr. Zdeborová said, “is that I think not only have we answered this question in the context of this problem. But more importantly, we have discovered a tool that can be applied across the board for many other problems.”