Rigidity and Flexibility in Geometric Constraint Systems

ICERM - January 2026

by Matthias Himmelmann

Geometric constraint systems (GCS) are used to model a wide range of geometric objects. These structures come with natural constraints, such as distances, angles, coplanarity, volume, or tangency, that are invariant under Euclidean isometries, namely translations, rotations, and reflections. GCS arise in numerous applications, including structural engineering, crystallography, soft-matter physics, and biochemistry. Two particularly important properties associated with GCS are rigidity and flexibility. We call a GCS rigid when the constraints do not allow a given realization to move beyond its ambient isometries. Otherwise, it is called flexible, indicating the existence of a continuous deformation of the structure. Rigidity and flexibility are therefore dual concepts: establishing either property automatically determines the other.

Geometric constraint systems (GCS) are used to model a wide range of geometric objects. These structures come with natural constraints, such as distances, angles, coplanarity, volume, or tangency, that are invariant under Euclidean isometries, namely translations, rotations, and reflections. GCS arise in numerous applications, including structural engineering, crystallography, soft-matter physics, and biochemistry. Two particularly important properties associated with GCS are rigidity and flexibility. We call a GCS rigid when the constraints do not allow a given realization to move beyond its ambient isometries. Otherwise, it is called flexible, indicating the existence of a continuous deformation of the structure. Rigidity and flexibility are therefore dual concepts: establishing either property automatically determines the other.

Rigidity Even for simple bar-joint frameworks given by embedded graphs with edge-length constraints, deciding rigidity is computationally challenging. For this reason, stronger conditions from various mathematical fields are typically employed. These criteria naturally lead to distinct algorithmic approaches, which motivated the development of the easy-to-use and general-purpose Python package PyRigi [1] for analyzing the rigidity and flexibility of bar-joint frameworks. The field of rigidity theory can be traced back more than 200 years to Cauchy, who proved that all simplicial convex polytopes are rigid. Building on this classical result, we use a combinatorial criterion based on the rank of the constraint system’s Jacobian to show that almost all realizations of convex polytopes with edge-length and facet-planarity constraints are rigid [2]. However, this rank criterion is only sufficient but not necessary. For example, we show that the regular dodecahedron is rigid, even though it does not satisfy the Jacobian rank condition.

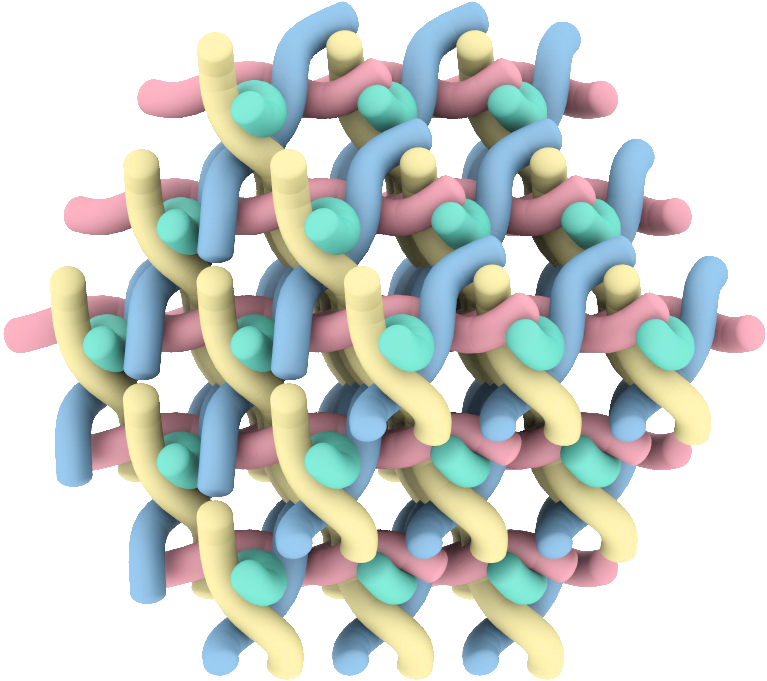

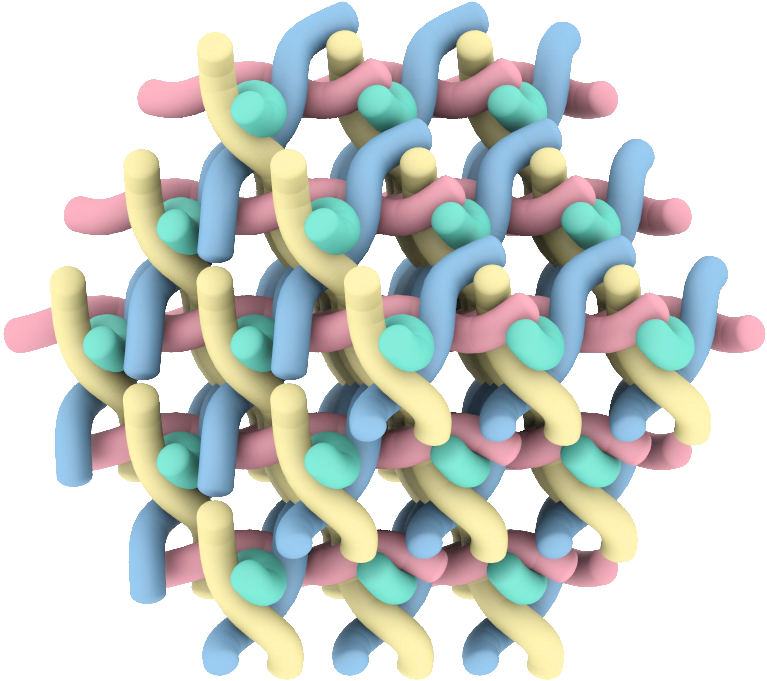

Flexibility Not all geometric constraint systems are rigid. In fact, Kempe’s Universality Theorem guarantees that for every algebraic curve there exists a bar-joint framework whose motion traces any bounded subset of the curve. Using a combination of Riemannian optimization and numerical algebraic geometry, we are able to robustly and effectively approximate deformation paths [3] by computing metric projections onto the constraint set. This approach has already enabled us to compute deformation paths of complex geometric materials, such as cylinder packings. A particularly compelling example is the Σ+ cylinder packing (see Figure), which is responsible for the water exchange in skin. We demonstrate that it extends hyper-auxetically [4]. Specifically, when stretching the material in a fixed direction, it instantaneously expands faster in its orthogonal directions, making it a particularly attractive target for metamaterial design.

[1] Matteo Gallet, Georg Grasegger, Matthias Himmelmann, and Jan Legerský. PyRigi — a general-purpose Python package

for the rigidity and flexibility of bar-and-joint frameworks. 2025. arXiv: 2505.22652 [math.MG].

[2] Matthias Himmelmann, Bernd Schulze, and Martin Winter. Rigidity of polytopes with edge length and coplanarity

constraints. 2025. arXiv: 2505.00874 [math.CO].

[3] Alexander Heaton and Matthias Himmelmann. “Computing Euclidean distance and maximum likelihood retraction maps

for constrained optimization”. In: Computational Geometry 126 (2025). doi: 10.1016/j.comgeo.2024.102147.

[4] Matthias Himmelmann and Myfanwy E. Evans. “Robust Geometric Modeling of 3-Periodic Tensegrity Frameworks Using

Riemannian Optimization”. In: SIAM Journal on Applied Algebra and Geometry 8.2 (2024). doi: 10.1137/23M1559075.