Effective Computation With Hourglass Plabic Graphs

ICERM - January 2026

by Christian Gaetz (UC Berkeley), Oliver Pechenik (U. Waterloo), Stephan Pfannerer (U. Waterloo), Jessica Striker (NDSU), and Joshua P. Swanson (USC)

Many students believe they should always expand their algebraic expressions. Yet computations are often easier if we don’t expand too early and instead remember the meaning of fragments of complex expressions. Consider the calculation of the determinant. The classic expansion formula has \(n!\) terms and is impractical beyond toy examples. But if we, for instance, spot linear dependence, we can immediately conclude the \(n!\) terms will all cancel without actually doing any laborious, error-prone arithmetic.

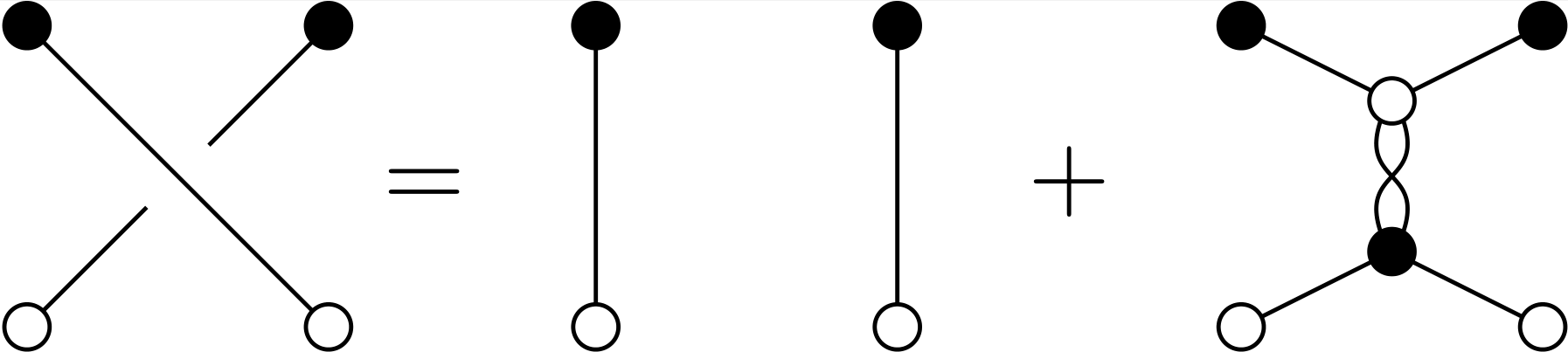

Algebraic expressions are not the only model of computation. A beautiful and deep area of mathematics, closely associated with theoretical physics, uses diagrams rather than numbers as its basic building block. There are many diagrammatic computational models; one of the most fundamental encodes the “representation category of quantum \(\mathfrak{sl}_n\)" in certain diagrams drawn in the plane. For example, we encode the \(n\)-by-\(n\) determinant as a “pinwheel” with \(n\) edges poking out of a central node. Things like the Plücker relations between determinants can then be understood diagrammatically as certain rewriting rules.

A basic question when assessing any computational model, diagrammatic or otherwise, is whether you can determine when two expressions should be considered equal. The first interesting case for us is \(n = 2\), which goes back roughly 100 years to 1932 work of Rumer–Teller–Weyl. Indeed, their actual application came from chemistry and configurations of atoms with bonds. In this case, every diagram can be directly reduced to a combination of diagrams where no edges cross. The condition that no edges cross remains true even after rotating the diagram. This results in a “rotation-invariant” basis, often called the Temperley–Lieb web basis.

A spectacular series of developments involving theoretical physics, knot theory, and quantum algebra around the 1980’s revealed the importance of the sln diagrammatic calculus. The next interesting case of the equality testing problem, \(n = 3\), was solved in the mid-1990’s in pioneering work of Kuperberg [5]. He introduced a remarkable rotation-invariant basis, roughly consisting of trivalent bipartite planar graphs embedded in the disk without squares or \(2\)-gons. While the broad shape of a diagrammatic computational model for general \(\mathfrak{sl}_n\) has been known for decades, a complete list of relations for arbitrary \(n\) was only proved in 2012 by Cautis–Kamnitzer–Morrison [1]. Nonetheless, the problem of finding a practical web basis for equality testing remained open for \(n ≥ 4\) for roughly 30 years since Kuperberg’s work.

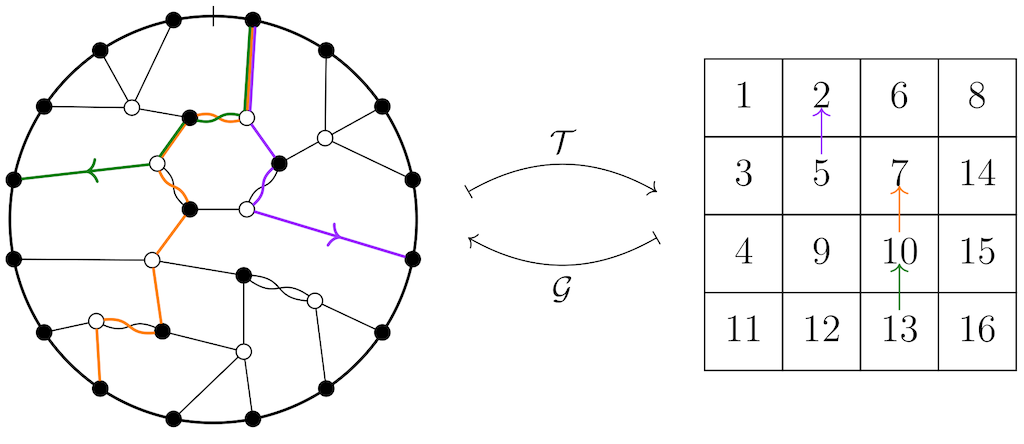

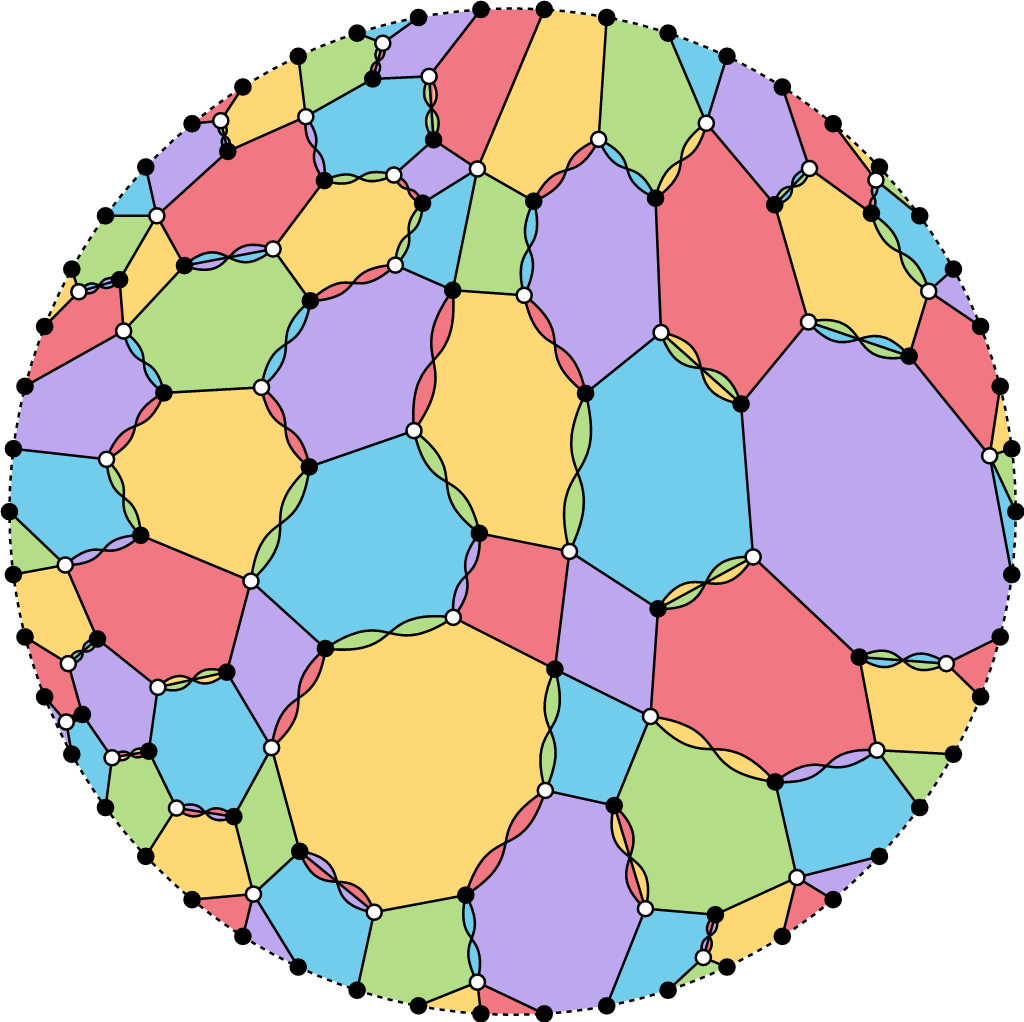

With support from ICERM in its Collaborate@ICERM program, we made breakthroughs on this problem [2, 3, 4] by introducing hourglass plabic graphs and solving the \(n = 4\) case. The resulting algorithm gives a super-exponential speedup over the naïve expansion algorithm. The heart of the construction involves a combinatorial bijection between hourglass plabic graphs and tableaux, as in Figure 2.

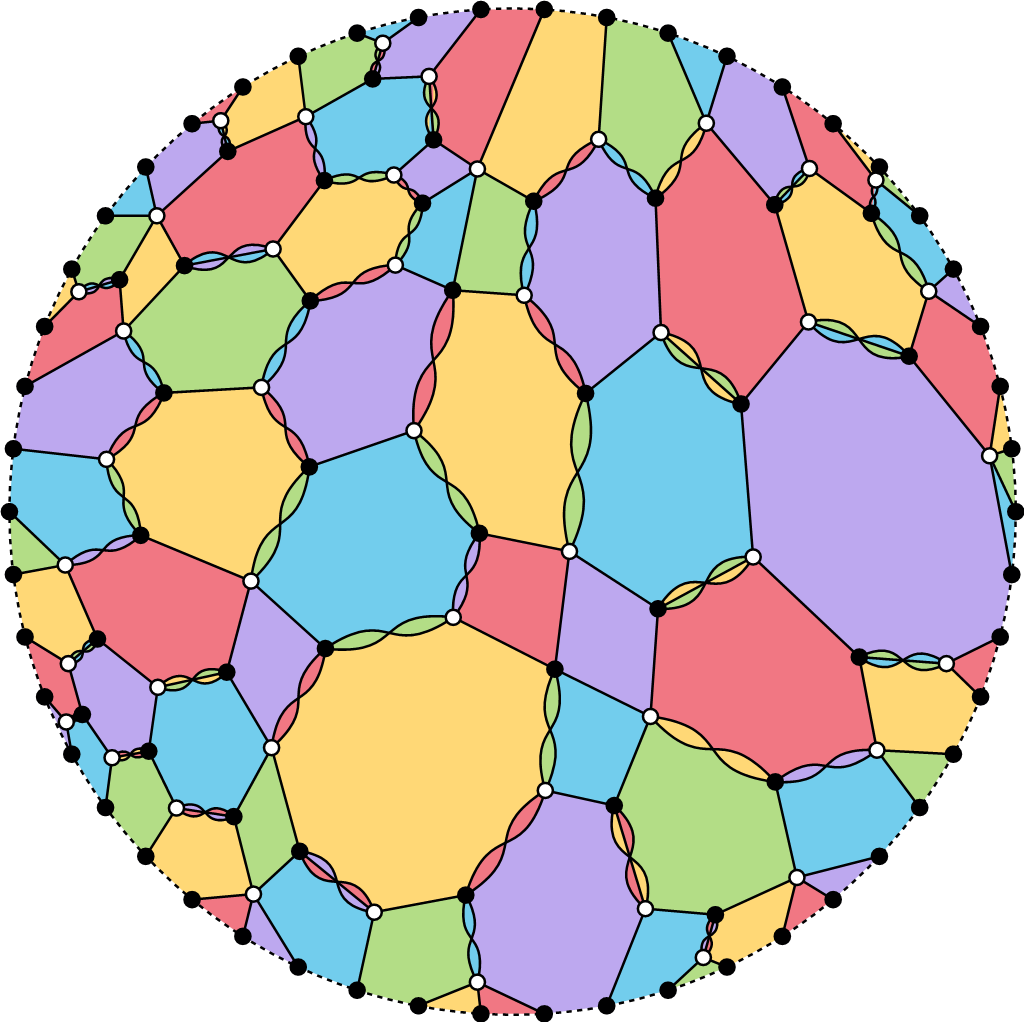

This work also reveals many remarkable connections to algebraic geometry, topology, representation theory, quantum algebra, and statistical mechanics. In fact, ICERM hosted a Topical Workshop in December 2025 focused on connections between webs and other research areas; the logo was the \(n = 5\) hourglass plabic graph shown in Figure 3.

We look forward to making further progress on higher rank web bases in our upcoming Collaborate@ICERM this summer.

References

1. Sabin Cautis, Joel Kamnitzer, and Scott Morrison, Webs and quantum skew Howe duality, Math. Ann. 360 (2014), no. 1-2, 351–390.

2. Christian Gaetz, Oliver Pechenik, Stephan Pfannerer, Jessica Striker, and Joshua P. Swanson, Promotion permutations for tableaux, Combin. Theory 4 (2024), 56 pages.

3. Christian Gaetz, Oliver Pechenik, Stephan Pfannerer, Jessica Striker, and Joshua P. Swanson, Rotation-invariant web bases from hourglass plabic graphs, Invent. Math. 243 (2026), no. 2, 703–804.

4. Christian Gaetz, Oliver Pechenik, Stephan Pfannerer, Jessica Striker, and Joshua P. Swanson, Web bases in degree two from hourglass plabic graphs, Int. Math. Res. Not. IMRN (2025), no. 13, rnaf189, 23 pages.

5. Greg Kuperberg, Spiders for rank 2 Lie algebras, Comm. Math. Phys. 180 (1996), no. 1, 109–151.